The Forgotten Evacuation of Wake Island

[By Retired Commander Tom Beard, United States Coast Guard]

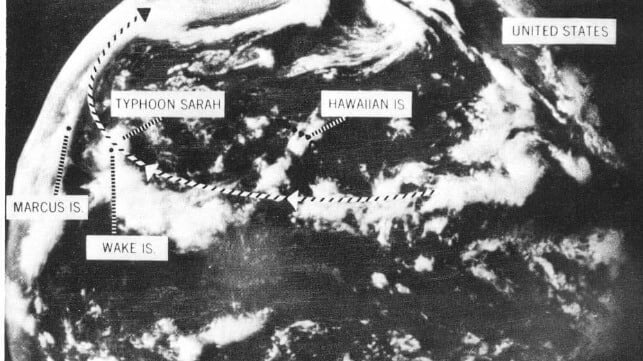

At 10:40 p.m. local time, Super Typhoon Sarah’s core smacked Wake Island, located in the South Pacific. With winds recorded at 130 knots and higher gusts, the island suffered a total loss of electrical power, disabling the air traffic control tower, all airport facilities, air-route traffic control center and all aviation navigational aids. Typhoon winds demolished all non-reinforced structures, including a “typhoon-proof” building. Witnesses noted refrigerators tumbling down streets and pianos disappearing. According to reports, the island’s infrastructure damage was nearly complete with the loss of all housing, sanitation systems and freshwater supply.

In spite of the physical destruction, personal injuries were limited to just seven victims. Six were minor and treated on the island. The single serious injury occurred to the Coast Guard commander’s wife, Ann Harrington. A piece of windborne lumber came through a window and struck her in the chest. She was quickly airlifted to Honolulu and Tripler Army Hospital for treatment. Of the island’s 2,000 residents, plans began for immediate evacuation of 560 dependent women and children.

During the Vietnam War, Wake Island supported a busy air terminal with an air-traffic control center. The island’s airport served as a major refueling point for civilian and military aircraft transiting the Pacific. Immediately following passage of the typhoon’s eye, a joint Federal Aviation Administration/U.S. Air Force task force undertook an urgent restoration of navigational aids and airport facilities to hasten a return to service for this critical mid-Pacific air terminal. The Air Force scheduled the airborne delivery of a portable aircraft traffic control tower and navigation transmitters. Planning also included scheduling air transportation needed for the evacuation of non-essential island residents.

Sunday, September 17

While the Air Force made plans, the Coast Guard took action, deploying a C-130 to evacuate severely distressed and homeless women, children and infants. The three duty pilots at Coast Guard Air Station Barbers Point launched an HC-130B Hercules aircraft at 4 a.m. local Hawaiian time, or 3 and a half-hours after the storm’s passage over Wake Island. All of the men had begun their duty day at 8 a.m. the day before, following a full workday. I, the fourth member of this ready crew, “rode the desk” at Barbers Point as mission coordinator at the Coast Guard Search and Rescue (SAR) Center. Most details of this story come from my recollections and all times are approximate. Documents noting Coast Guard details during this period are scant or nonexistent. The SAR file folder, which likely became recycled paper decades ago, leaves only this writer’s faltering memories and a few old newspaper clippings as perhaps the only record of this event.

The mission for this Coast Guard humanitarian response was to evacuate as many storm-displaced survivors as quickly as possible. At that early hour in the morning, the HC-130B was not prepared for a passenger transport configuration, nor was it usually, as its primary mission was as a long-range search and rescue aircraft. The aircrew quickly tossed packaged troop seats (snap-together aluminum tubing and fabric seats) into the aircraft in the minutes before the long-distance flight’s departure. The crew planned to install the seats in-flight during the first leg to Midway Atoll.

Calm followed in the SAR Center following the C-130’s 4 a.m. launch, with its first fuel stop at Midway expected in about five hours. However, I got an urgent radio message from the aircraft commander already halfway to Midway. The seat belts were not in the troop-seat packages! He asked, “Can seat belts be obtained from Midway during refueling?” Early morning calls ensued. My answer to the aircraft commander: “No seatbelts for the troop seats at Midway.” On landing at Midway, the flight crew obtained some long ropes they used as makeshift seatbelts by weaving them through seat frames and across laps.

The second five-hour, 1,200-mile leg from Midway to Wake Island began after a quick refueling. Out-of-service navigation aids on Wake left the crew without the benefit of electronic guidance to their destination. Being the first aircraft to arrive, the C-130 landed about 11 a.m. Wake Island time or just over 12 hours following the storm’s passage. Without the traffic control tower, the crew had no benefit from navigational facilities, instrument approach aids, or warning of flooding or debris on the storm-ravaged runway.

After landing at Wake, assembled survivors trundled aboard the C-130. Aided by the aircrew, women, children and infants crowded into the vast cargo space — all were emotionally devastated, wet and traumatized. After closing entry doors and starting engines, crying babies could not compete in volume with the engine noise endured in the plane’s cargo bay. These bewildered souls were destined to spend the next 12 hours in this noisy cavern of metal and exposed plumbing, designed for trucks and inanimate cargo, not passenger comfort. I recall the number of evacuees being 96 individuals.

The C-130 returned to Midway after five hours and stopped for refueling and a comfort stop for passengers. From their pooled personal funds, the C-130 aircrew purchased diapers; baby food; milk formula; water; food; and snacks, and provided for other passenger needs for the last leg to Honolulu. The take-off occurred at 7 p.m., with almost five hours remaining before a midnight arrival at Hickam Air Force Base.

I recall the Coast Guard aircrew members recounting how they spent most of their time working in the cargo area with survivors by cradling and feeding babies, changing diapers and playing with children to ease the stress on their mothers.

Among my duties at the SAR Center was to put out a press release to local news reporting sources. This was a time when a Coast Guard press release received little interest from the local press and none from national news services. Seldom did any event, at least those released from our SAR desk, ever reach print or television. A press release was merely one more of the SAR duty I performed. For this assignment, I contacted the local TV station, radio stations and newspaper with a quick summary of events. Check. Duty done.

Monday, September 18

The Coast Guard C-130 touched down at Honolulu International Airport, adjacent to Hickam Air Force Base, at about midnight after 20 hours of mission time. An Air Force C-141 touched down immediately after it.

Earlier, the Air Force had dispatched the C-141 to help in the Wake Island evacuation. This transport aircraft departed Hickam at about 2:30 p.m., or 10 hours after the C-130 took off from Air Station Barbers Point. The jet-powered cargo aircraft was capable of a direct round-trip flight. Its leg to Wake Island took 5 1/2 hours, where it boarded its capacity of male construction workers not required for the island’s recovery. The return flight placed the C-141 landing right behind the C-130 arrival at Honolulu International. Both aircraft were taxiing to park and discharge passengers. Hickam tower instructed the C-130 to “hold” and wait for the C-141 to pass.

Responding to my earlier press release, a TV news crew and reporters covering this budding national news event had arrived at Hickam’s main gate shortly before the planes landed. They inquired security personnel about the flight inbound with survivors from Wake Island. A gate guard called the Air Force public affairs office, which, in turn, knew nothing of the evacuation flight. Soon, an Air Force public affairs officer met the news crews only then to learn of the event. He called the tower asking it to direct the taxiing C-141 arriving from Wake Island to park at the number one VIP spot, where floodlights could illuminate the scene for television coverage, giving the best coverage of the haggard survivors of Wake Island.

Meanwhile, the Coast Guard C-130 was directed to follow the C-141. The C-130’s designated parking spot was a quarter mile from the welcoming activities and media reception. Its location was an unlighted and abandoned section of the airfield. No assistance was provided to help the Coast Guard crew — which had been on duty for 28 hours, including a dozen hours caregiving needy passengers and babysitting. The Coast Guardsmen’s next task was to locate help to deplane their passengers in total darkness and arrange transportation from their isolated parking area. These survivors missed the lights and fanfare of a welcome home — and more importantly — assistance and relocation. In the distance, they could make out the lights and media coverage surrounding the C-141’s return.

After seeing to their passengers’ needs, the C-130 crew launched once again, this time for the 15-minute trip home to Barbers Point. The men had been flying for almost 24 hours, and the aircraft needed cleaning and refitting to its SAR configuration to be ready within 30 minutes for the next potential SAR launch.

Except for the aircraft commander, Lt. Jim Webb, I cannot recall the names of members of this crew. At the time, a C-130 crew would typically be about seven — eight with an extra pilot. These men performed humanitarian service beyond the call. I am unaware of any recognition, nor do I ever recall, seeing any letters or other acknowledgments for this Coast Guard aircrew’s heroic deeds. As with so many other Coast Guard missions, it was just another duty night.

This article appears courtesy of The Long Blue Line and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.