Should Australia Rebuild its Merchant Navy?

Australia’s vulnerability to maritime trade disruption is well recognized. International shipping moves some 99 per cent of the nation’s traded goods by volume worth A$755 billion in 2021, and provides not just prosperity but also vital resources such as 91 per cent of the country’s fuel and 90 per cent of its medicines. Canberra’s options to manage these risks range from resource stockpiling to electrifying transport systems. But for any extended disruption to regular trade, some seaborne supply of critical resources will be necessary. And here the nation faces a melancholy trifecta.

In a crisis, only Australian-flagged (i.e., controlled) ships could be requisitioned to sail for Canberra. Yet of the some 6,000 vessels conducting our international trade, only four of any size (over 2,000 tonnes of cargo) are Australian – insufficient to assure supply. Further, the armed risks to trade are growing. For non-state actors, a key danger was once lightly armed pirates in skiffs. Today, the Houthis have added various suicide drones, Anti-Ship Cruise and Ballistic Missiles (ASCM and ASBM), and helicopter assaults into the mix, and similar groups will likely copy them. For states, Australia’s key risk is a blockade by China, which has amongst the world’s most powerful navies and is both still growing that force and now deploying it into Canberra’s backyard.

The capability to manage such risks is decreasing. Fundamentally, securing supply means protecting merchant ships by using naval forces – commercial vessels simply lack the sensors and weapons to intercept drones, ASCMs and ASBMs. Yet the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) can’t fully crew even its ten frigates and destroyers suited against complex threats, let alone protect 6,000 merchant ships. Which is why Canberra depends in particular on the United States Navy, still the world’s premier fleet, to maintain a peaceful global maritime order.

Yet the US Navy’s contribution is in doubt. The fleet is at its smallest and oldest in decades, and fighting the Houthis has depleted weapons stockpiles, so if new dangers arise, it’s unclear if they will be met effectively. Further, the Trump administration has shown it’s willing to cease being a global security provider, or to charge exorbitantly for its services. So even if the US Navy is able, Washington may be unwilling – without a price. Note that a year of Houthi-focused US Navy operations cost around A$8 billion, and if you think the United States wouldn’t ask for that back, just call Zelenskyy.

So, Canberra needs more large Australian-flagged vessels while dramatically improving the RAN’s capability for their defense – and ideally with low cost, risk, and crewing impacts. Fortunately, there’s a way: an optionally armed Merchant Navy.

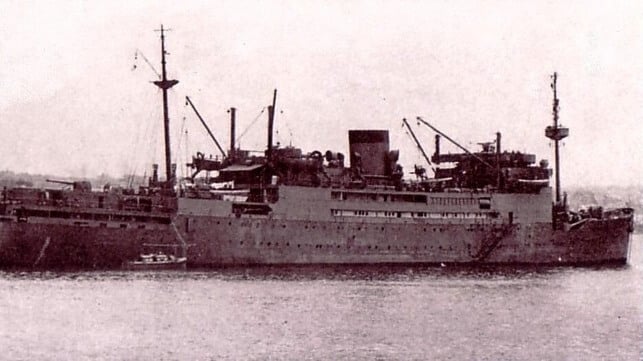

A country’s Merchant Navy are the commercial vessels under its flag, able to be requisitioned during crises. Australia once had a Merchant Navy, and the 2023 Strategic Fleet Report proposes (without using the term Merchant Navy) just such a body of vessels. It argues for 12 (and ideally 50) larger ships, with these commercially owned and operated, and Canberra paying some A$8 million per ship annually to cover Australia’s higher operating costs. While the report doesn’t mention arming such vessels, there’s a history of doing so from Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships (DEMS) equipped for limited self-defence to Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMC) with heavier weapons to guard convoys. A Merchant Navy of 50 ships (though Canberra’s only agreed to 12) optionally armed with easily removable weapons as DEMS and AMC has great merit.

DEMS could mount Phalanx gun and SeaRAM missile systems atop minorly modified 20- and 40-foot shipping containers. These systems together can address the most probable threats, and have self-contained sensors, computers, and weapons – minimizing integration risks. For convoy protection, an AMC could equip Mark 70 launcher units, each with four large missile cells in a 40-foot container. The 1500-square-meter cargo surface area on a modestly sized AMC could notionally provide 50 launchers with 200 ASCM to hold Chinese ships at bay (Beijing’s most potent Type 55 destroyer holds at most 112 ASCM), with this arsenal remote-controlled by RAN escorts, again minimizing integration risks.

This approach offers huge cost savings. Phalanx and SeaRAM are each A$25-40 million, and while the AGM-158C ASCM for the Mark 70 costs some A$5.5 million apiece, 200 fit on an AMC that costs Canberra nothing to buy versus 32 on a Hunter frigate that’s A$3.7 billion. Also, as containerized weapons could be easily added or removed, fewer units could be bought and then swapped between vessels. Further, 50 vessels at A$8 million each would cost A$400 million annually, noting eight ANZAC frigates were A$374 million.

Finally, the RAN crewing impact is favorable. DEMS ships had a few naval personnel to operate their weapons, while AMC replaced their regular staff with military crews. So, DEMS would likely need some three RAN personnel and AMC around 20-30. For 50 ships this means 150-1,500 personnel; in contrast, a single Hunter has 183.

So an armed Merchant Navy has enormous potential, though it wouldn’t replace warships. The Hunters (and others) cost so much, including due to their exquisite sensors, computer systems, and damage resistance. But DEMS and AMC offer a cheap, crew-friendly way to enhance Australia’s supply lifelines. As such, they deserve a close look.

Dr Victor Abramowicz has worked for over 20 years in the national security sector, across government, industry, and academia. He specialises in defence policy and strategy, military technology, security relations in East Asia and Eastern Europe, and military history. He is also the Principal of Ostoya Consulting, which provides advisory and business development services to a range of companies in the defense sector.

This article appears courtesy of The Interpreter and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.